Only an hour into our days ride and I was already off and pushing. I was internally cursing the unrelenting steep climbs, the loose potato sized rocks of the road surface and the 10cm of fine dust that was it’s top coat. All of it seemed to be conspiring against me. Each step forward, heaving the heavy bike, was thwarted by the kinetic nature of the road itself. And, unlike many times before, we didn’t even have ourselves to blame for adventurous (or just plain silly) route choices. This time we were on a road. An actual road. A road used by vehicles. A road designated with a National Highway number. Yet, it was unlike any other ‘highway’ we’ve ever ridden before, in fact it was more like the old-road bridleways of home that we love – albeit much steeper and far dustier.

We were following the Mid-Hills High Road. An old mountain trading route that spans the entirety of Nepal, from the Western border all the way to the country’s far reaches in the East. The route traverses the entirety of the Himalayan Mid-Hills Range. For over ten years the road has been in construction, with plans to turn the old mountain road into a highway, but it’s an ongoing project. A seemingly never-ending project. Before we set off, we wondered if we would be too late, if the road would already be highway, meaning we would have missed the rural charm and instead by greeted by asphalt and traffic. We needn’t have worried. Yes, some sections were asphalt, but for the majority of the time the term ‘road’ was a very loose description, and we welcomed the bagginess. It also very much felt that the attempts to turn the road into a highway were an uphill battle, with each monsoon season evidently washing away the previous years hard work, and each dry season cracking the foundations, turning the rubble to dust and blowing it away down the valleys. It felt as though the construction workers were in a perpetual battle against Mother Nature; trying to tame the wild thing she is, to contain a force that cannot, will not, be overpowered or outwitted. Don’t tell them, but I’m on her side (always will be!). And it made for some great adventurous riding.

In places, it seemed that the main users of the road were the heavy, filthy, clattering construction trucks, who needed to rebuild the washed out road in order to be able to build the road, so it could be washed out again. A bit of a crazy loop to be stuck in, but that’s humans for you! Most of the time, whilst ever we were away from the larger towns, there were very few other users of the road, we maybe saw the occasional local on a moped with skills to rival that of a great dirt bike rider; we might perhaps have to dodge the one bus of the day bouncing down the hillside or swerve a Mahindra pickup truck overloaded with goats, but generally it was just us and the dust. So, yes, ‘road’ was a slightly misleading term.

I mean, come to think of it, the whole name is pretty misleading. The ‘mid-hills’ might have you thinking of rolling hills of green, but these were definitely not that. In any other country these would be mountains, serious mountains. The route saw us climbing between 1000m – 1500m every day, at an altitude up to 3500m. And although there is no mistaking that the route did make us climb ‘high’, it didn’t stay there for long, and just as soon as we crested the top of the hill, we could be sure we’d soon be rolling back down to the lush green, farm filled valley floor. It was like being back on the Peru Divide again, and we loved it.

With each hill we climbed, we were treated to misty views of valley after valley, fading away into the distance, edged by precarious villages on steep mountain sides connected by gravity-defying suspension bridges. A landscape of neverending, overlapping layers. Beautiful.

Sadly, the poor air quality, pollution and excessive dust (thanks again to global warming for the lack of rain/snow this year) meant that despite knowing they were there, we only ever glimpsed the High Himalayas once. In a whole month of heading West, we saw them once! We even traversed a ridgeline known to provide uninterrupted High Himalayan views for 30km, but all we saw was the grey, smudgey haze of pollution filled air – and we were in the rural hills, not near the cities. So we did well to hold on tight to our yoga mantras of ‘no expectations’ and enjoyed the extent of the views that we could see.

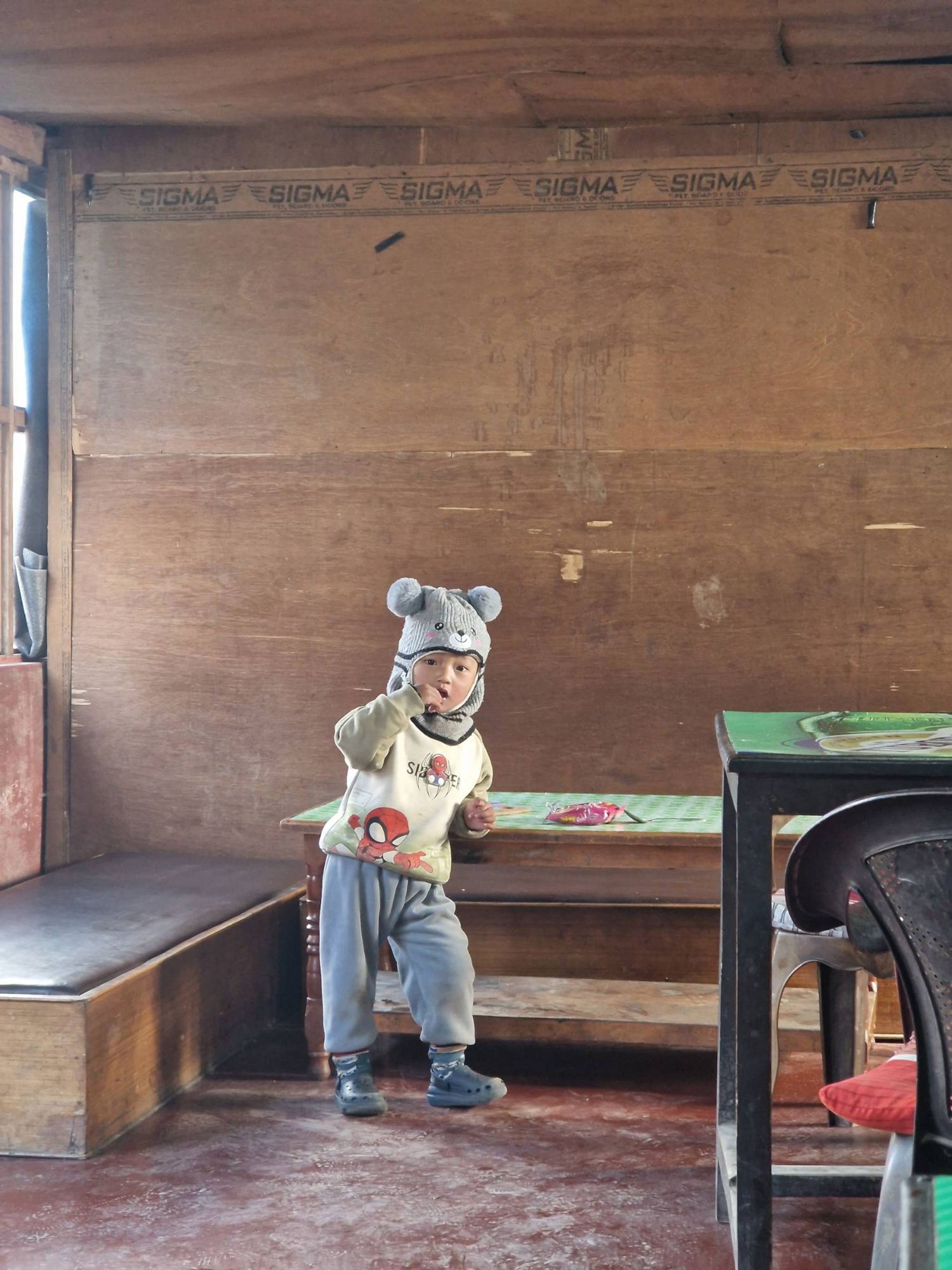

In Nepal you can never be down in the dumps about these things for long though, as right around the corner will be a local with the biggest smile and the warmest welcome. In every country we have visited so far, there is something very special about mountain villages and the people who call them home, and this was the case in Nepal too. We were always greeted with such joy, shouts of ‘Where are you from?’ or ‘Welcome to Nepal’ rang in our ears as we passed by with big waves and smiling faces. Children ran alongside the bikes enjoying the chase – wild and free.

We rarely plugged our headphones in for fear of missing out on the joy that we received with every interaction. Locals suprise at seeing us often gave way to confusion about why we were choosing to ride a bicycle when we could afford a motorbike. Their puzzlement would grow when we explained we preferred to work our lungs and our legs. For those who already have such a physically hard life, it seemed absurd to them to want to choose a physically exhausting mode of transport, let alone travel on it day after day for two years.

The villages of Nepal have a richness that cannot be bought. It’s a cliché and one that I’m only able to band about because of my privilege, I know. But it is something that I feel so deeply. The villages have heart, community and connection in a way we can only dream of in the UK. These are things that cannot be measured by GDP or on a national or political scale. Nepal is a poor country by the calculations of GDP, and many Nepalis we met spoke about the frustration and anger they feel because of the corruption and useless nature of their government. The lack of infrastructure and social care makes this evident to see. But we also met a number of Nepalis who had the surprising opinion that many individuals in Nepal have a lot of wealth, despite outwardly appearances. We saw hints of this in the huge number of families where sons or daughters were studying at University abroad, in the UK, Australia or Japan, and who were paying the full international student fees, which is not a small sum. We also met many Nepalis who had family members working abroad, sending home much larger incomes than they could ever hope for in their home country. As family means so much in Nepal, this must be an unimaginably tough reality to bear both for those going and those left behind, but with all things, the Nepalis shoulder it all with a smile.

Rolling into a village often felt like stepping back in time. Life was simple. Traditional. Largely unchanged for generations. The further West we reached, the more there was very much a sense that this was a forgotten land; villages locked between steep mountain sides, protected, yet cut off, by the hills they call home. The only access via the bumpy road we had travelled. With the huge number of ethnic minorities living in these far Western hills of Nepal, each valley had a different feeling and atmosphere slightly different to the last. Traditions and life were visibly different even a few kilometres apart, from the crops they were growing, to the colourful prints and patterns of material of the women’s saaris.

They definitely don’t see tourists in these hills very often. But regardless of all this, the introduction and obsession with the smart phone, and TikTok in particular, seems to have taken hold in even the most rural of places. I’m pretty sure I can retire and make my millions as a TikTok phenomenon now, given the number of times I was filmed for the purposes of a TikTok video!

Life in these forgotten hills was physically hard but seemingly happy. We were told that most of the Nepalis in these villages owned their own homes. Most seemed to have some land to grow vegetables and to feed a buffalo or goats for milking. The water ran clean from the mountain sides, and filters for water were pretty common, either in individual houses or at the village drinking tap. Primary and Secondary education is free in Nepal, and the huge number of English speaking children attest to that. The villages also had a strong sense of community, whether between women all heading to the tap to wash clothes together, or men playing board games in the street, there was purpose and togetherness in their lives that often seems so lacking back in the UK.

Village life meant we were also never far away from an incredible meal, or a cup of sweet masala chai (tea). Every roadside stall offered veggie samosas for a few pence, meaning that Ted was about 50% samosa by the end of our month of riding. With Dahl Baht (lentil soup, rice, greens, pickles and salad – all with free refills) being the national dish of Nepal we honestly think Nepal might be the cyclists land of dreams. We know many other tourists often get bored of eating Dahl Baht all the time, but with every region in the more rural areas having their own variation of the dish it meant we never got sick of eating the same thing, and always looked forward to filling our bellies with the fresh, veggie-filled, nutritious meal at the end of every day. Nepalis don’t really eat breakfast – they put so much sugar in their morning masala chai that it’s enough to keep them going until late morning – so we found carrying our own usual supplies of coffee, oats, chai seeds and fruit to be pretty handy, and it meant we could avoid the inevitable disaster it is to set off riding with empty tummies.

We had heard that you didn’t need a tent in Nepal and although we carried ours, just in case, we didn’t need it. We always managed to find a bed for the night – sometimes it was in a lovely homestay where you felt like a long-lost relative welcomed home; sometimes it was in a grotty guest house where we kept our finger-crossed we wouldn’t catch anything from the bedsheets; sometimes it was a cold, impersonal, concrete block of a hotel room; sometimes it was a storage space in the back of a restaurant with a couple of cots that was more like a barn than anything else – but there was always something when we asked around.

Wherever it was, we were always grateful for a safe place to sleep with a roof over our heads, even if the shower was an icy cold bucket of water and the window was still waiting for the glass to be fitted. But our favourite night was our stay with Rammani and his family.

We were on yet another long, dusty climb; our legs tired after an already monstrous day of climbing. The sun started to dip dangerously close to the horizon, the shadows of the valley and trees growing ever-longer around us, as we valiantly tried to push on to reach the next village we knew would have a guest house. It was only another 10kms away, but here in Nepal it was the elevation that mattered, not the distance, and at this time in the evening, the elevation profile ahead of us was not in our favour. We paused to discuss the inevitable reality that we probably weren’t going to make it before nightfall. Just as we did, Rammani appeared on his motorbike. After the usual Nepali joy-filled greeting, we asked if he knew of anywhere to stay that was closer than the guest house we had been aiming for. Soon enough, Rammani had kindly invited us to stay with him and we were following the taillights of his motorbike down the dusty back-roads. Despite having no fore-warning about the arrival of two tired, disheveled and dusty cyclists, Rammani’s wife, Sita, welcomed us with a huge smile, her hearty laughter and two cups of tea – we immediately felt like family. We were fed like kings by Sita, who served us up a delicious Dahl Baht and we were even treated to warm buffalo milk, milked fresh by Rammani himself. Fortunately for us, Rammani was the Head Teacher and English teacher at the local school so were able to chat away and exchange stories about life in the UK and life in Nepal. They laughed at the notion of us meeting as teenagers and marrying for love a few years later, we marvelled at how in love they obviously were when they hadn’t met before their wedding day. They were curious about the (mis)conception that everyone in the UK is happy because it is a wealthy country, we were admiring of their simple, quiet, sustainable life on their homestead. We heard how the caste system of Nepal (despite discrimination based on caste being legally abolished in 1963) is still very much an influence on the socio-economic reality of their lives, which to us felt so unbelievably archaic.

It was an evening we will never forget. Time and time again we are blown away by the kindness and generosity of strangers who become friends. And it always makes us question why we in the UK are so closed off, so guarded, so un-trusting of others in comparison. Are we all so busy and important that we can’t take the time to talk to the shop assistant in the corner store? Are we all so deceived by the news that we believe everyone in our neighborhood to be villains? Are even those in need of a safe place to stay for a night to be looked upon as though they are not to be trusted? I can’t image how different our trip so far would have been if these perceptions prevailed the world over.

After a month of riding Westward through this special forgotten region of Nepal, it was time for us to think about heading back to Kathmandu. For some boring visa related reasons, and some not-so-boring ‘we might be arrested for carrying our GPS tracker’ type reasons we would not be crossing the border into India, and instead would be heading back to Kathmandu to fly out. But that wasn’t before we managed to squeeze in a couple of days in the beautiful Bardiya National Park. It’s a park known for its elephants, rhinos and tigers, and we were hopeful of seeing all three as we set off on our guided walking safari. Don’t worry, we were armed with a stick(!) in case any creatures thought we looked like dinner, but sadly it wasn’t our day and we didn’t see anything, although we did hear a tiger roar which is pretty cool, not something you hear every day!

We then braced ourselves for a 22 hour bumping bus journey back to Kathmandu, which was then followed by a bout of food poisoning, and finally after all that, we were ready to leave Nepal. I mean, I say that, but I don’t think I was really mentally ready to leave Nepal, Kathmandu yes, but I already knew I would miss Nepal. A county I had wanted to visit for so many years, a country that had delivered in every way, and a country I really hope to come back to one day – if only to get a proper look at those High Himalayas.

Leave a reply to Tony Cancel reply