Almost immediately, Laos felt different to Vietnam. We were only a few meters away from that arbitrary line in the road that defined the border and already; goats roamed the streets, a huge gold painted Buddhist statue towered over everything, mounds of bananas defied gravity piled high on mopeds, all the houses were wooden huts on stilts and no roads, other than the main highway, were paved.

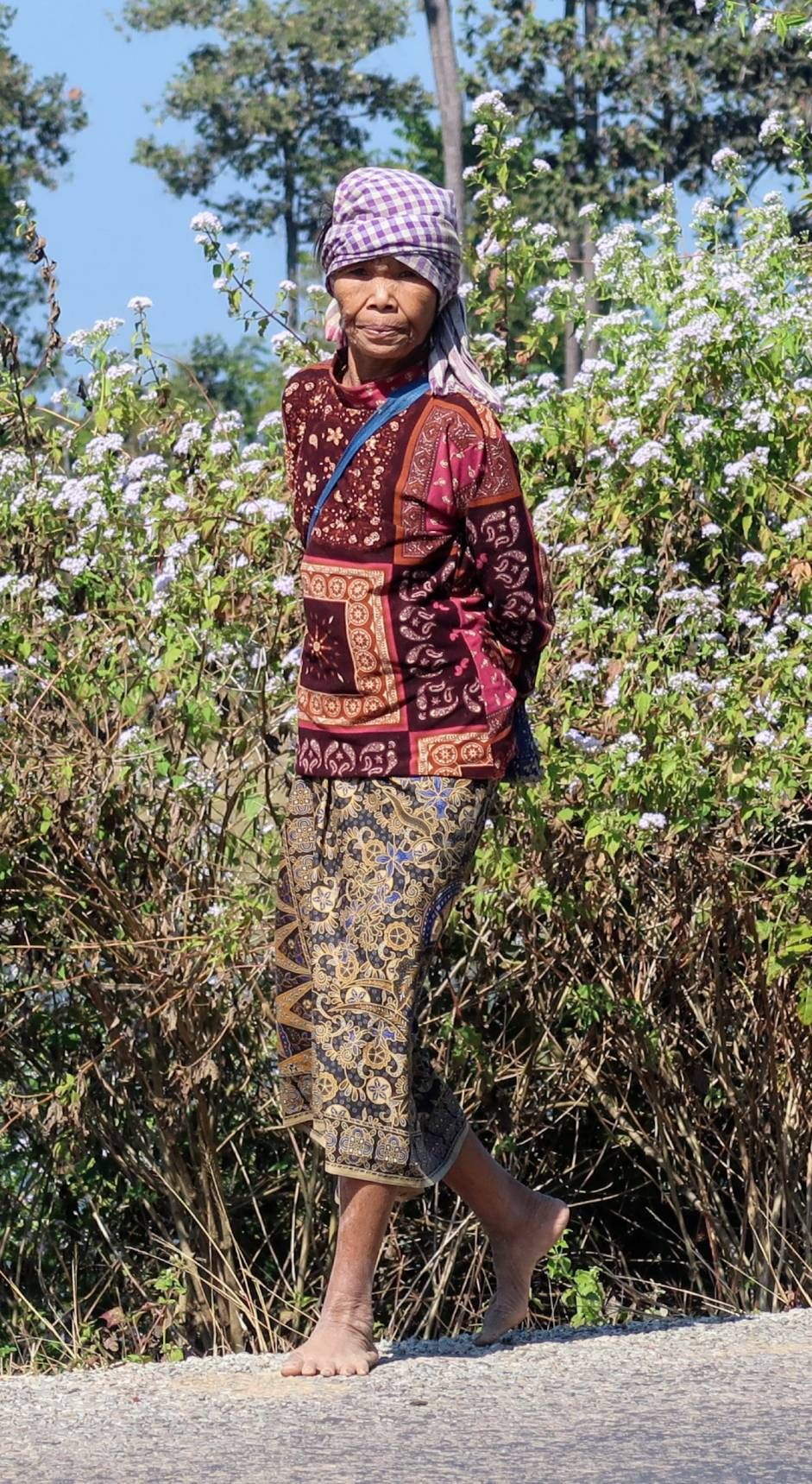

The increase in shoeless feet walking the high street of the border town of Dansavan was a stark and sad indicator of the poverty in this area.

And if we thought the people in Vietnam were friendly, then, wow, the people in Laos were on another level. The children in particular were something else. We could hear their joyous shouts of ‘hello’ and the thumping of their bare feet on the red mud floor as they ran towards us, minutes before we saw their outstretched waving arms and huge smiling faces. Even though we were riding on the highway, the children all came running out to greet us. Excitedly jumping up and down at the side of the road, pulling silly faces and wanting to collect ‘high fives’ like they were sweets, seemed to be the favourite things to do. We became accustomed to hearing their shouts and quickly glancing around us to find out where they were coming from – sometimes from the steps of houses, sometimes from the fields and sometimes even swinging out from the trees they were climbing. They seemed to have a superpower that enabled them to spot we were different, that we were outsiders, from miles away. Even with our faces covered by our sunglasses and buffs (to protect us from the sun and pollution), even though many people here cycled on heavily laden bicycles, they knew we were not one of them, and they were so excited by it. It was so special to be able to share this joy with them and enthusiastically return their waves and shouts. Each and every time, we caught their infectious smiles and we carried them with us as we rode along.

It is truly incredible to think that the people of Laos are so warm and friendly to outsiders, given the country’s history. The huge number of empty artillery shells being used as gate posts and decorative features outside villages, homes and businesses highlights the history that the rest of the world believes is in the past, but that locals live with in the present, every day. You can’t visit Laos and not be horrified by the reality that these warm, smiling people living simple, rural lives were subject to ridiculously heavy artillery fire during the Vietnam War. So much so, that it has the unenviable title of the most heavily bombed country in history. With over 2 million tonnes of bombs dropped on the country during the war, it equates to nearly a ton per person (or so the internet tells me). The unexploded artillery continues to kill people in Laos every year, and in an area where so many people live below the poverty line, relying upon the land to feed themselves and their families, this is a heart-wrenching reality to witness. Seeing the huge white off-road 4x4s, branded with logos from the Halo Trust, brought feelings of hope, but it does make you question how on earth humans have created this? How have we come so far down this line that this is now the reality? How have we got it all so wrong?

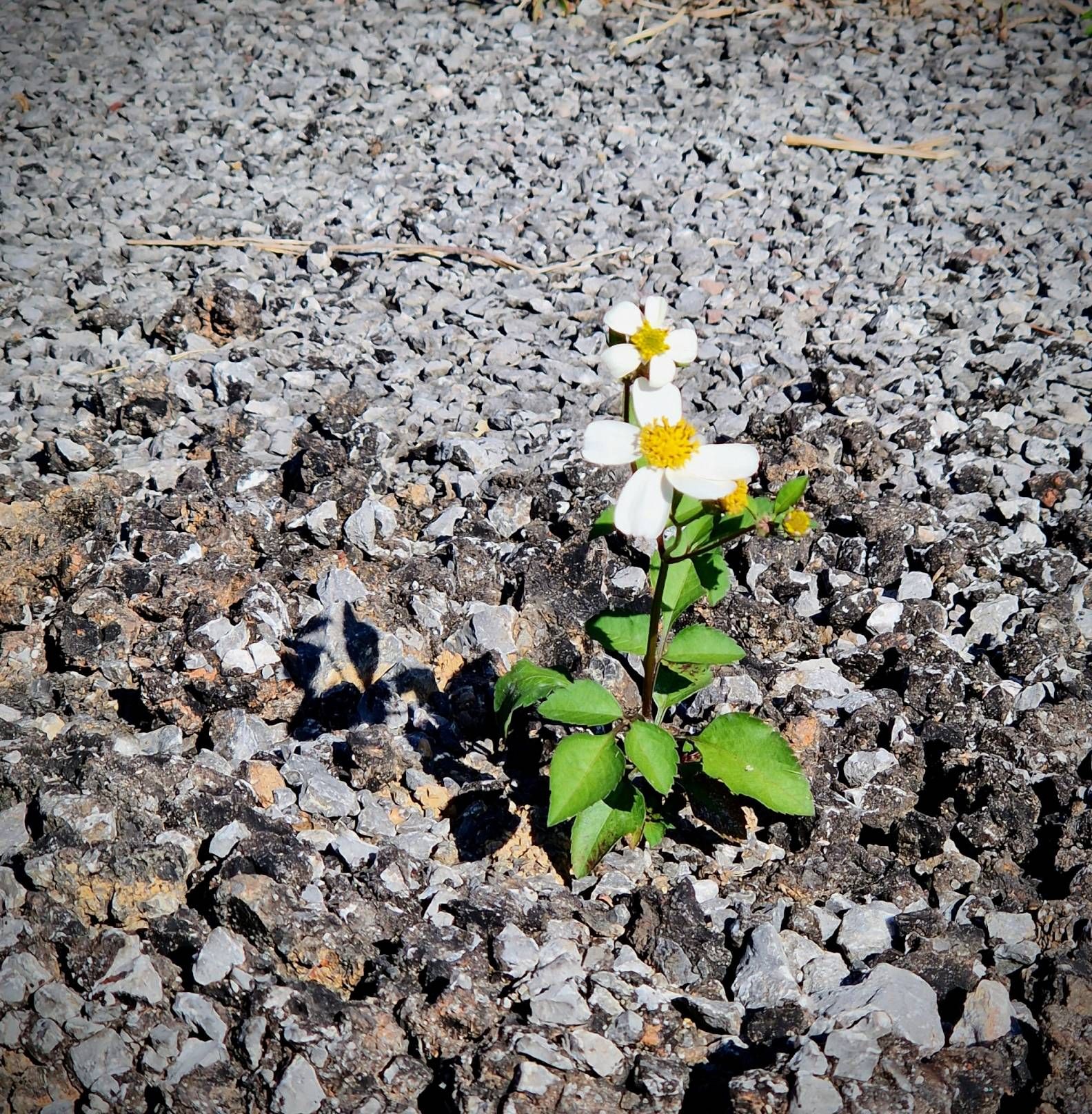

We found our first few days in Laos hard. Seeing the poverty. Experiencing the filth. Riding through ever worsening air pollution from burning rubbish. Seeing the skies darken with the plumes of smoke from slash-and-burn agriculture. Stuck on the edges of the one, truck-filled highway. Noticing the banana plantation workers red-raw faces (from the pesticides perhaps, or the sun exposure?). Observing the lack of biodiversity, no bugs, no birds, no animals (other than the omnipresent chickens and goats of course!).

It felt like we were picking up weights one by one and adding them to the mental load we had been collecting since first arriving in South East Asia. And by now we were substantially laden, the burden felt heavy.

It’s hard for me to write. No one likes reading about the unpleasant bits, the bits that make you feel uncomfortable. They want swashbuckling, daring and romantic adventures on a bicycle. They want the picture postcards that they too can escape to and visit to get the perfect Instagram-worthy photo. People don’t want to read about the bits behind the fake tourist facade. I also don’t want to give you the impression that I’m moaning. I’m not. Travelling by bicycle is absolutely the most perfect mode of travel (in my mind!) because we get to experience all these things, not in spite of it. Being immersed in the reality of a place doesn’t take away from our trip – it is what makes it. But it doesn’t mean that being there isn’t hard, it doesn’t mean that the feeling of overwhelm is invalid and it doesn’t mean that seeing the destruction of the environment can be shrugged off with a reminder that ‘at least the UK is saving the world with it’s ban on plastic straws’!!

Seeing the kaleidescope of the ravages of war, poverty, biodiversity loss, plastic pollution, irresponsible agricultural methods, air pollution, mono-culture, CO2 emissions, noise pollution and water pollution highlights just how messy this all is. It’s complicated. It’s not easy. It can’t be quickly fixed. It makes me want to get my white, privileged ass back on my bike and ride away from it all – but now that I’ve seen it, I can’t just ignore it. It comes with me. It is now part of me. I know it is a sentiment that Ted shares, but feels more acutely given his job working in sustainability.

But I don’t want to give the wrong impression of our time in Laos, actually, out of all the three countries we travelled through in South East Asia, Laos was our favourite. There was a simplicity about it that I loved. Once we had the chance to turn off the highway, the riding was really enjoyable. The hills were dramatic and beautiful. The temples were bright and cheerful, often overflowing with well-tended flowers and impressive trees. It felt authentic. Rural villages preserved a lot of traditional ways of life, and not for tourists but for themselves. It was calm. There was no rush or choatic hubbub. And the power of the smiles and joyous laughter truly was a thing to behold.

I also can’t possibly finish this post without mentioning Hans. We first bumped into Hans, a fellow cycle tourist, from the Netherlands, on our final day in Vietnam. Hans also endured all the unpleasantness of that memorable day in the rain, with the climb and the trucks so we all shared an instant bond. We hadn’t met any other bicycle travellers for months, and when it’s just the two of us, with no one else to talk to, it can often feel like we are stuck in an echo chamber, not knowing whether we are just getting bogged down in things or whether our thoughts and feelings are only natural. So to meet Hans, and experience his down-to-earth, wise and upbeat approach was a real pleasure and was a welcome break from our bubble. Despite waving goodbye to each other on several occasions, changes in plans, changes in routes and changes in cycling speeds meant we kept bumping into him throughout our time in Laos.

For us, our time shared with Hans was a great experience and reinforces how much community means to us. We were sad when the time came to say what we knew would be our final goodbye, on our last morning in Laos.

We had received a very generous offer from a friend to stay at her place in Bangkok, whilst she was back in the UK for the Christmas break. So with the prospect of a few days rest pulling us onwards, we changed our plans (again!), got our heads and legs in gear and made a beeline to the border with Thailand. They ended up being the first pedal strokes in covering the 1000kms to Bangkok before New Year in less than ten days. We ended our time in Laos as two hot and tired cyclists, after a very long and dusty day with another border crossing behind us….

Leave a comment