Japan – Part One of Two (or should that be Chapter 2, Part 1 of our round the world antics, who knows!?)

This time last year we were in Europe, just settling in to life on the bikes. A life where our only permanence is the bikes, each other and the little green dome we call home. Despite all our previous bikepacking and travelling experience, it was a steep learning curve. If someone had asked me back then whether a year later I would still feel like we were climbing that curve I doubt my answer would have been yes, but, at times, it definitely is. Our time in Japan highlighted that to us in bright, lit up, neon colours.

We were ready for a change of culture and we knew that, just like our jump from Peru to the USA, the contrasts would be stark, but nothing can ever really quite prepare you for the reality of it. Change is always hard. Even when that change is longed for and anticipated, even when there’s no resistance to it, even when we think we have had time to adjust (thanks to a few days in Tokyo) it still takes a little while until we feel re-centred. I always seem to spend a few days, or weeks even, feeling like the smallest thing can threaten to derail me. I suppose it’s only natural that when nothing around me feels familiar anymore, every decision requires even more thinking about, even more energy is used up considering possible consequences and all my senses are on overdrive trying to absorb as much knowledge about my surroundings as possible. This is what I’m able to rationalise and logically recognise with the beauty of hindsight. But at the time, when you are stood in the third convenience store of the day, tired, hungry and photographing every item through Google Translate in order to work out if the packaged product in your hand contains what you think it does, or whether it’s yet another pork ball and fish flake concoction, it’s easy to feel very overwhelmed, totally useless and a bit lost.

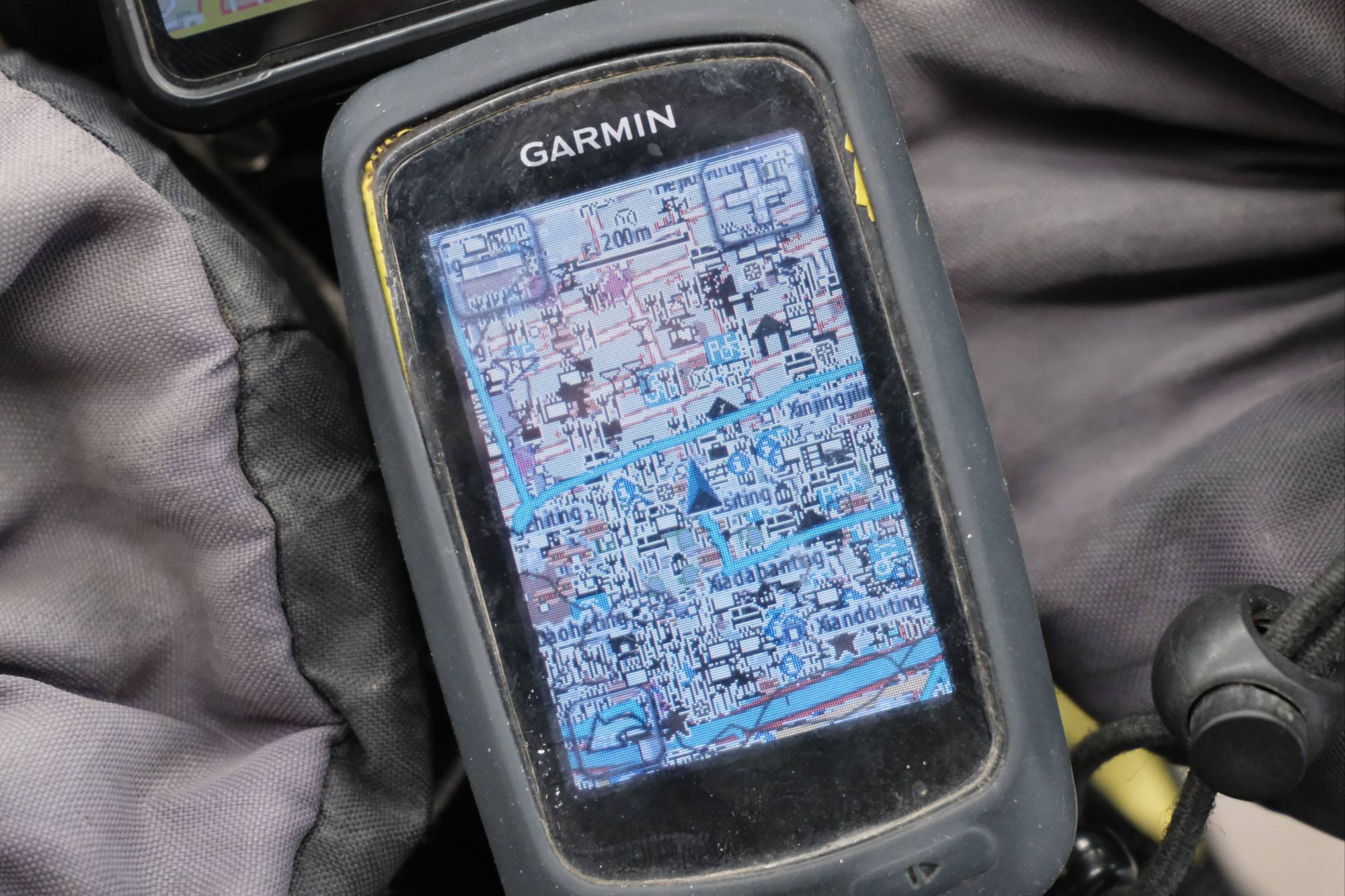

That’s not to say we’ve not learnt a lot in the last year. We absolutely have. Our successful navigation out of the mega metropolis that is Tokyo was a nod to that. We put together a route from a mish-mash of places, some small back-roads, lots of river paths (a bit like a canal towpath in the UK) and some cycleways, loaded it onto our Garmins and followed the black line. Which all sounds very easy, but the truth is that there is a lot more to it than that. You have to keep your wits about you for traffic, for other cyclists and pedestrians; you have to have one eye on the route and another on the road (the only benefit of my slightly squiffy eye!); you have to know when to jump and when to stick when it comes to traffic lights (which are literally every 50m in any town here in Japan); you have to listen out for trains crossing; you have to dodge the bollards and fence posts that spring from nowhere (also loved here in Japan); and you have to remember to look about and enjoy the sights you’re passing by, all whilst repeating the mantra ‘ride on the left, ride on the left’, whilst keeping those legs turning, lungs pumping, shoulders loose and Ted in sight ahead of me.

We initially rode northwards out of Tokyo towards Oarai from where we would jump on the ferry to Hokkaido (the most Northerly of the four main islands of Japan). The high humidity and muggy heat meant our clean fresh clothes were soaked and stuck to us in a matter of minutes – another thing to have to adjust to. The days are also much shorter here, and at 5.15pm it’s as though someone starts turning down the dimmer switch on the sun – the light snuffed out entirely by 5.30pm. In our initial few days this caught us out a few times. It’s not that we can’t ride in the dark, we have our dynamo lights all set up to allow us to do this, but we would always rather set up camp and eat in the last of the daylight so we can see what’s around us before we settle down for the night. But that first day after leaving Tokyo, it came as a bit of a suprise and again added to the slight feeling of unease. We stayed at a cheap campsite that first evening, aiming to stay at a campsite or somewhere we know tents are permitted (rather than wild camping) is another tactic we have learnt to use, where we can, in order to allow us some piece of mind on the first night after a culture shock or country shift. Even when we arrived at the campsite in the dark, we still had to try and get used to the super-size of the bugs – especially the spiders – which seem to compensate for the small size of everything else here in Japan.

Once we’d settled into our little green dome for the night, ensuring it was spider free, we set about looking at the route for the following day, and tried to book a spot on the ferry to Hokkaido. After jumping through several website hoops and filling in form after form of information online, we kept getting a simple ‘computer says no’ type response because our details were not successfully translating into the Japanese system. It was frustrating. It was winding Ted up so much that in the end, he simply turned off his phone and said we’d just ride there and sort it out in person. I always feel so much more uncomfortable doing this, and would prefer to have a plan and a reservation, but this trip has definitely taught me that sometimes things are better dealt with by trusting things will be okay, looking a person in the eye and enjoying human connection, rather than expecting the little box of my smartphone to sort everything for me. So as we rolled onto the ferry the following day with no problem, after our visit to the ticket booth at the ferry terminal, I was grateful that we had placed our faith in people rather than the computer algorithm. It was a lesson we would revisit many times over during our month in Japan.

Our time on Hokkaido was like visiting Autumn. The moment we disembarked from the ferry, we instantly regretted wearing only our shorts and t-shirts, which were not cut out for the colder temperatures, and stopped to dig out our warmer layers. The leaves on the trees were a rainbow of colours and the air was fresh and damp. Another change for the body to adjust to. The mornings were misty and cold, the mid-days warm and the temperatures plummeted again as the sun set every evening. We slowly re-adjusted our body clocks to echo that of the sun, to make the most of the short day light hours, but it meant dealing with a wet tent every morning.

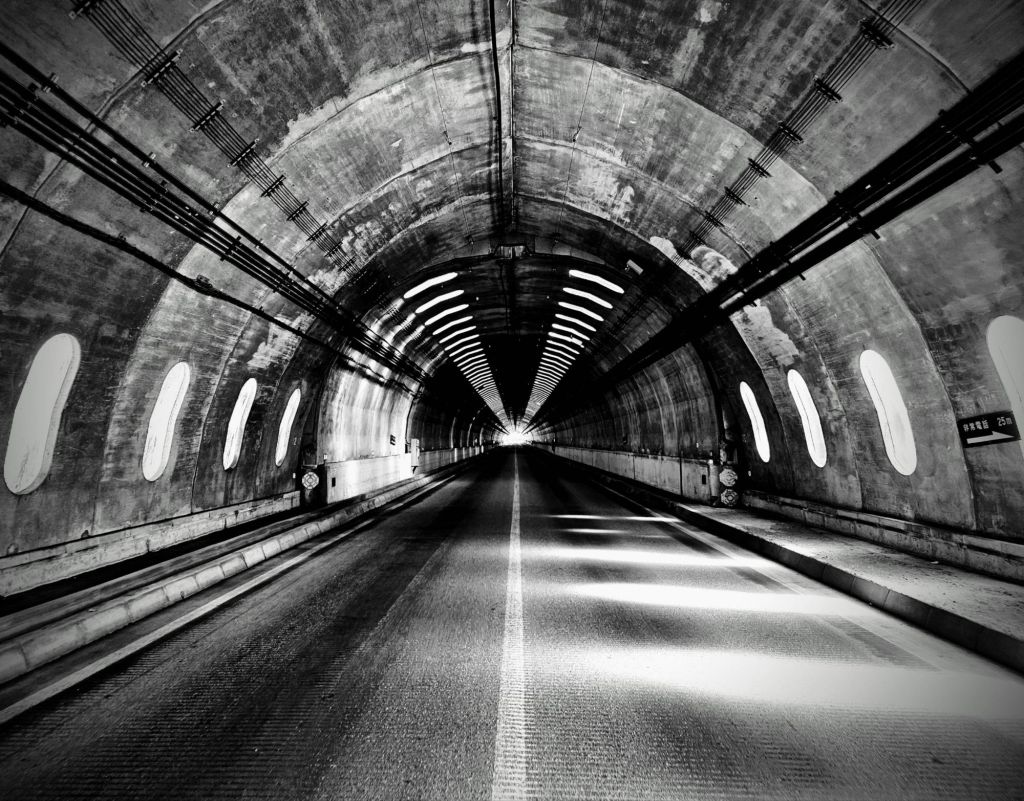

We slowly got used to the huge amounts of concrete infrastructure that are ever-present here in Japan, even in the most remote places. We slowly braved riding through tunnel after tunnel, where the noise of one single car sounds like a jet engine, and the sound of multiple vehicles is so deafening it’s disorientating. We even started to get used to the language barrier. Very few people speak English here in Japan, and I think we had become a bit complacent in the USA and Canada about how much easier it makes everything, but we slowly improved our hand-signal, sharades and Google Translate combo, which is no doubt an invaluable life skill. Slowly, slowly, little by little we adjusted to the changes.

We wiggled about a bit on the island of Hokkaido, and if we’re being honest, we didn’t quite know where we wanted to go or what we wanted to do. We just knew that we wanted to try and experience a taste of all the four main islands of Japan during our time here, and with Hokkaido being the most Northerly, it made sense to start there to avoid the incoming winter, which can see metres of snow fall as early as the beginning of November.

We are used to planning our routes on back-roads, seeking out the path less travelled, but this didn’t really work out as we hoped. Each gravel road we tried to follow ended in an impassible barrier, a washed out landslide, a road deteriorating and disappearing to nothing, or my personal favourite – being submerged under a reservoir. So we chopped and changed our route ideas many times over. We tried out some quieter roads and quickly got tired of their wiggly-getting-nowhere-nature. Then we tried out some of the highways and immediately remembered why we don’t like highways. So we tried to find as many paved back-roads as we could, but it all felt a bit purposeless, heading in one direction then deciding on something different. But the beauty of the trees, mountains, volcanoes and rivers of Hokkaido ensured we enjoyed our time there nonetheless.

We also enjoyed our first Onsen (Japanese hot spring) and it was a very welcome deep defrost after the cold temperatures we had experienced. We were a little nervous before we went in. There are generally lots of rules here in Japan. Lots of signs and posters, covered in lots of rules. Rules about anything and everything. In advance, we had read about all the etiquettes you must adhere to in the Onsen, so as well as overcoming the British awkwardness of being totally naked around a bunch of strangers, we had the added nervousness of making sure we remembered all the rules on our first visit. But we need not have worried. It turns out that the female Onsen was like a serene spa, of calm, quiet, gentle women each one being polite and courteous, and I just ensured I did as they did, it was blissful. Ted on the other hand said the male Onsen was all about the little towel (not a euphemism!), but Ted didn’t have a little towel (again, not a euphemism!). Ted said it was all about washing the towel, rinsing and drying the towel, not putting the towel in the water, putting the towel on your head, wringing out the towel, flailling the towel about – like he said, all about the little towel.

We made our way back to the largest Japanese island of Honshu by an overnight ferry, and again submit our bodies to a change in temperature as we returned to the tropical humid heat we had experienced on leaving Tokyo. It made riding a hot and sweaty experience, and at night we would have to peel our sticky bodies off our roll mats every time we turned over.

Honshu is a lot more built up than Hokkaido, it feels like one giant urban sprawl, interspersed by small fields of growing rice or perfectly neat vegetable patches between houses. We saw very few young people in any of the smaller towns or villages, the vegetables all being grown by the older generations, who despite their age were bent double over their immaculate rows of cabbage or onion or carrots, working the land by hand. It was impressive to see, especially when we sat outside a Michi-No-Eki (a local roadside station) one morning with our coffees in hand, watching all the local elderly people bringing small baskets and crates of fruit and vegetables to sell in the shop that day. It seemed like a great way to collectively sell local produce, and by the sound of the chatter and laughter amongst them all, there is obviously a great community spirit that accompanies it.

The urban sprawl does, however, make camping feel a little more difficult.

We are used to reading maps for contour lines, rivers and woods to try and find a possible place to camp, so reading a map for parks, slivers of green space and public toilets is all new to us. If I’m being honest it feels a lot less like we are adventurers and more like we are just homeless. But we’ve never been disturbed or asked to move on, we’ve always felt safe and we’ve often been met by smiles of intrigue from the elderly locals on their morning walk/ bend-and-stretch-throw-your-arms-in-the-air workout routine. I definitely don’t enjoy it as much as camping out in the wild though and I know it will take me a long time to get used to. Sometimes I think the language barrier is actually helpful in this context – especially for a self-conscious, conflict-avoidant, people pleaser like me – it means that I have no idea what people are saying, or muttering under their breath, as they walk by with an unimpressed expression on their face. I can just smile and nod as though they are just passing the time of day or talking about the weather.

The thing we have been surprised with though is how little interaction there has been generally. We know it’s a cultural thing, but the lack of eye contact, heads down privateness, or eyes-that-see-right-through-you whilst the locals are all in their own individual worlds has felt a bit strange. Its given us a sense of not hostility, but definitely lack of human attachment or emotional connection. We recognise that historically, with Japan being a collection of islands that rarely saw outsiders it is not part of their culture to be open, especially to visitors, but there is a sense that this is changing with each generation in an ever connected world. And maybe it’s also because you can rarely see facial expressions as a lot of people still wear masks. Even when outside in fresh air, even when on their own, even when wearing gloves, even when in their own car with no-one else with them the masks are on. It’s sad to think that this is the legacy COVID has left here – it definitely has left an undertone of fear and disconnection. We can’t help but feel that the lack of exposure to everyday microbes will be more of a hindrance than a help to the immune system, but they don’t seem to recognise that.

That’s not to say that we haven’t had some amazing help when we’ve needed it. A day that sticks in my mind is the day we arrived in Kyoto. It was a day of non-stop torrential rain, a day of sticky temperatures and high humidity, where we opted to buy cheap convenience store ponchos rather than face putting on our heavy-duty raincoats in the vain hope of them being cooler – They weren’t! We were soaked to the bone within minutes, and fingers turned to prunes after about half an hour of riding.

We had nothing planned for accommodation in Kyoto and because of the rain we didn’t know whether we would reach it that day, or get sick of being soaked and call it a day early. Surely the city was big enough for us to find accomodation if we did reach it in a day, right!? Well it might have been, if it wasn’t a Saturday.

In the end, trying to find anywhere to stay in Kyoto was a total nightmare. We had reached the outskirts of the city by mid-afternoon and decided to push on to the centre, using our usual approach of trusting the universe that something would work out. But after hours of riding around the city, asking at hotels and guest houses, as well as hours spent on the internet, we had no luck – absolutely everywhere was full. We did, however, stumble upon the most delicious Sri-Lankan curry restaurant – We had been day dreaming and chatting about how much we missed Sri -Lankan curry only a couple of days before, so this yummy veggie curry was definitely our manifestation and truly was what we needed in that moment.

The friendly owner of the small place called around some friends and all the numbers of guest houses he could find to check for availability, sadly without success, but it was such a kind gesture. He even suggested we book ourselves a karaoke booth for the whole night and just sleep in it. I mean, it wasn’t a bad idea, plus I would have been able to sing away on the karaoke machine to my heart’s content – Thankfully at around 9.30pm we finally found a hotel so it absolutely saved Ted’s ears from hours of my singing, but it was a stressful evening to say the least, and not what you want or need after a whole day of riding in torrential rain.

When we finally rode across the city to reach the budget busting hotel – in the continuing rain – we reached it only to find that they were not happy about our bikes being locked outside the hotel, not locked to the hotel, but just left anywhere near the front of it. The only, very unhelpful, thing they could suggest was that we needed to take it to an ‘official’ bike parking space, the closest of which was a 30min walk away. Whilst I calmly tried to explain, several times over, that this wasn’t practicable because all our luggage was attached to the bike, I kept just getting shown the iPad with Google Maps locations of the official bike parking spaces. Again, I would explain this wouldn’t work for us, and asked if there was anywhere in the hotel we could put them, or at the back of the hotel, or somewhere on the street, or next to the hotel bins – but each suggestion was met with an unsure look and confirmation that he would call the manager and ask, with every suggestion coming back with the blanket answer of ‘no’. It was almost as if he couldn’t possibly think of anything different, as though he couldn’t compute any concept of doing something that wasn’t a predetermined answer given by the iPad he was holding. Ted reached the end of his patience, he disappeared outside, took the bikes into a car park opposite the hotel and locked them up, returning into the hotel to explain he had sorted it. The hotel guy wasn’t happy about it, but we were shattered and beyond caring, we just wanted to crawl into the stupidly overly priced hotel bed and sleep – so we did.

After a day of doing the tourist thing in Kyoto – which was as much about seeing the unbelievable number and diversity of tourists, as it was about seeing the tourist attractions themselves – we rolled out of town towards Osaka and the coast beyond.

As dusk fell and we found ourselves pitching the tent next to the noisiest steel processing factory imaginable, I slowly realised that things didn’t feel so difficult anymore, it bizarrely felt kind of normal – We’d crested the wave of learning curve.

So our initial few weeks in Japan had been a bit more of a rollercoaster than we thought, but we were quick to remind ourselves that one of the reasons we set off on this trip in the first place was to get us out of our comfort zone. The necessity of being comfortable in the uncomfortable is something we’ve experienced so much of during this trip and although being uncomfortable never seems to get any easier, we find that we are much quicker now to recognise the feeling, acknowledge it’s okay, and accept it with a smile on our faces (well mainly on my face, Ted’s still working on his!)

Leave a comment