Our final month in Peru has been spent riding another iconic Bikepacking route, this time the Peru Divide. The route is famous for it’s stunning rugged mountain scenery, remote villages teetering on steep valley sides and climbing. Lots and lots of climbing. Then a bit more climbing.

The Peru Divide is so called because it roughly follows the geographical boundary of the watershed – to the East the water flows into the Amazon (and from there into the Atlantic), and to the West the water runs into the Pacific – pretty cool eh!? It’s essentially a month long traverse of the peaks of the Andes. When I first read about it a number of years ago, it immediately had me hooked and I knew that shoehorning it in to any world adventure would be a priority for me.

But reaching the starting point of the route in Abancay, we were both pretty exhausted and suffering from a severe case of skinny. Our muscles hadn’t had chance to rebuild or restrengthen, and we had both struggled with more on-off stomach bugs. It’s not how we wanted to start a route that we had both been looking forward to so much. So we did what any self-respecting bikepacker would do, and took an extra day off to eat and sleep and eat some more.

Thankfully for us, Abancay had an incredible market. Fruit and veg so colourful and ripe that we wanted to buy one of everything. The market hall also had a whole level of hot food stalls, and a whole section of fresh fruit smoothie stalls – Not the kind of food halls you get in the UK, where you never feel hipster enough to truly feel comfortable and the food is so expensive you leave still feeling hungry, but the kind of market hall where regular everyday folk go for simple, healthy lunches with a genuine dose of community served up with it. Perfect.

After our rest/eating day, we spent half a day standing in queues for Western Union, trying to get some more cash (an inevitable saga we have now come to expect, but still find frustrating) we finally left Abancay. The tiredness still lingered in our bones, and we were also a little apprehensive about not really feeling mentally ready, but we figured the first few days on the paved road would be a nice introduction – which they were.

It wasn’t long though before I started thinking that there were many divides (not just the watershed divide) that the Peru Divide was highlighting to us, and that perhaps there was more to the name than initially intended.

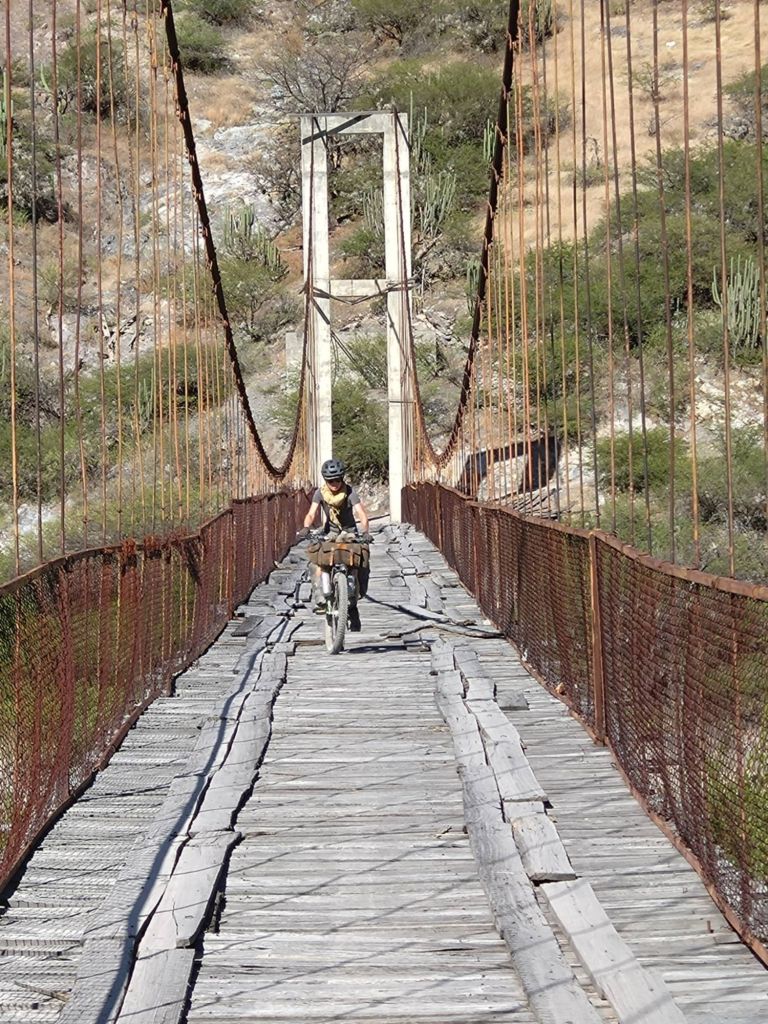

The first obvious divide was the physical geography. When I mentioned earlier that there was a lot of climbing, it turns out that all our time in South America so far, has merely been a warm up for our legs. The route encompasses one 5000m (ish) pass after another, and I soon came to learn that there is no ‘top’ and there is no ‘flat’ in the Peruvian Andes. Instead the whole route is a continuous collection of ups and downs. And I mean, serious ups and downs. Everyday roughly encompasses 1500m of climbing, only to be followed by a descent of a similar height. Its crazy, but gives you an indication of the geography here. A few days in to the route, when looking at our plan for the day, there was 16km – as the crow flies – between the village we started out from, and the village where we hoped to be able to find a shop, but the reality actually involved 60km of riding distance, 1000m down and 1200m back up to the otherside of the valley – I’ve never wished to be a crow before, but on that day, as I sweated my way up switchback after swicthback it’s all I wanted!

The mountains and canyons are like nothing we’ve ever experienced before. So steep and seemingly never ending. The riding isn’t technical, it’s all on dirt roads with varying quantities of chunky loose gravel, but this doesn’t seem to make it any easier, especially on the lungs that still let you know when you’re at altitudes over 4000m. The wiggly, winding, zig-zag roads cutting into the steep mountain sides are impressive to look at from an engineering point of view, but tough to ride – both up and down.

The upside is that all of those ups and downs provide day after day of spectacular scenery. It’s amazing to experience the change in environment as you descend – the vegetation turning more tropical and desert-y the lower you go, the temperature increasing, the number of bugs and birds growing as you get closer to each valley bottom before finally seeing the fast flowing, life giving river that created all this geography in the first place. We’ve got used to taking off layer after layer of warm clothes with each couple of switchbacks we descend. Being able to experience the landscape through travelling by bike is a real gift, as we feel so connected to the geography, environment and nature that we are travelling through. We are jolted by every bump in the road, we feel every prickly plant we sit on, we notice the wind chill as our goosebumps appear, we smell the lupins in blume, and boy do we feel every mountain we climb.

The route has also given us a greater understanding of the divide between mountain life and city life here in Peru. The mountain villages we have ‘tumbled‘ into have been pretty varied. Some have been seemingly self-sufficient and full of life with small fields of mixed crops all worked by hand, with cows, donkeys pigs, chickens and alpaca all roaming the hillsides and the village streets. Others have felt like ghost towns, no-one about and eerily quite other than the street dogs. Some have felt like they’re the leftover forgotten evidence of a once boom and bust industry or thriving mine, with old ladies sitting on doorsteps of mud brick houses idly passing the day knitting and watching the occasional truck go by. Others have had immaculately kept plazas thriving with life and food stalls, ladies feeding the village from gigantic steel pans.

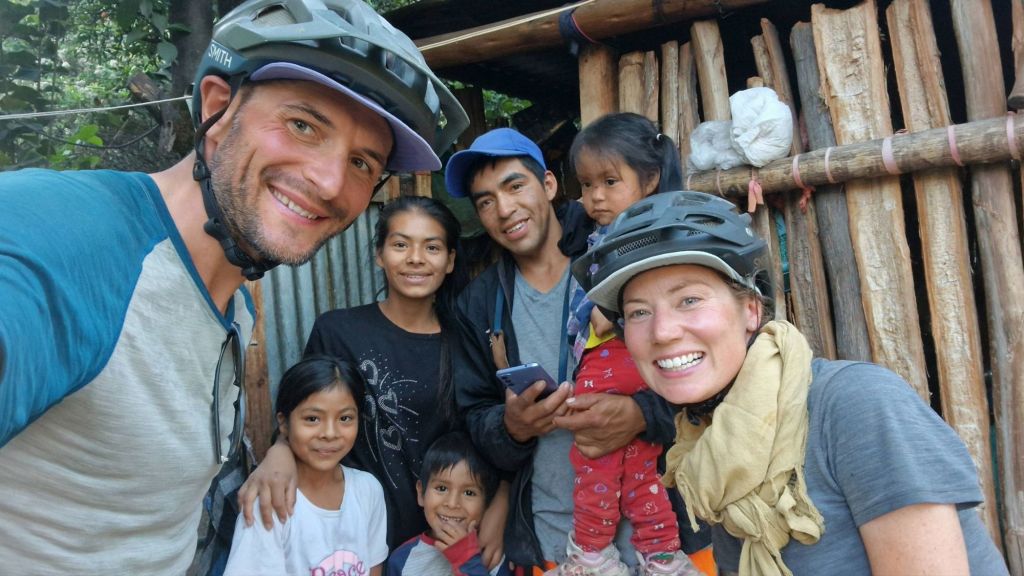

But the one thing the mountain villages all have in common is the warmth and generosity of their people. We have been welcomed with smiles, waves and curiosity. In one tiny village of Santa Rosa de Anta, at the start of a hot, sweaty, climb coming out of a huge canyon, we stopped to ask a young family if we could refill our water bottles from their outside tap. They invited us in, they gave us a bag full of about 15 oranges straight off their tree – juicy, sweet and delicious. They also handed us huge plates of food, with lentils and rice and salad. As we sat in the welcome, cool, shade of their one room we looked around at how little they had. Shelves made from crates and cardboard boxes attached to the walls, a small cot in one corner, a collection of toys that had seen better days strewn across the floor and the table that we were sitting at – handmade – along with the rickety benches spanning it’s sides. But the two young families who both lived in this one home, all had the biggest smiles and were so enthusiastic about our visit to their remote village. They invited us to stay the night with them, but as it was only mid-afternoon we kindly declined. They didn’t want any money or contribution for the food or oranges, they simply asked for a few selfies with us, which we happily provided. Such incredible kindness and generosity from those who really don’t have much to give.

In another village, this time mid-way up a leg and lung busting steep climb, we asked a local at the plaza if there was anywhere for us to eat, he walked us to his home. His wife happily offered to cook us some rice and eggs. We rested outside the house enjoying the warmth of the sun against the stone at our backs, and as she invited us in to eat at a small children’s table, we caught a glimpse of the open hearth stove she had been cooking our lunch over. It was like stepping back in time. Again, she initially didn’t want any money for the lunch she had prepared for us, but she did finally accept a contribution when we insisted a couple of times.

And these ladies, that we met on a mountain road, are a true inspiration. We heard them laughing and joking before we saw them. It’s rare that I ever feel tall, but despite the height difference, I came away from our meeting with these two ladies hoping to be half the ladies they are at their age. They were loaded up with their mantra’s full of heavy goods. Only four teeth between them, but so many smiles and jokes. Their infectious positivity brightened my day, and continues to do so every time I think of them.

When it comes to sleeping, the villagers are also incredibly generous. When we’ve happened to arrive in a village just before sunset (which is between 5:45pm – 6pm here, it’s so quick it’s like someone turns out the lights!) we have been walked from one side of the village to the other to be shown the accommodation, we’ve been invited to camp outside churches and inside community halls, we’ve been told to stay at Tambos (basic dormitories for local ministry workers), Campmentos (accomodation for mine workers) and shown to peoples spare rooms. Again, a true testament to the wonderful people here and the generosity of those who have so little.

But there is definitely a difference between the mountain folk and the city folk, in fact any area where locals frequently see tourists. In the cities, although the people we have met have mainly been very friendly, you get the feeling that they see outsiders more like opportunities, and less like people. They love to ask us how much our bikes cost. We’ve found that they tell little white lies of what you want to hear – so when they say there is hot water in the shower, it generally means there isn’t. In fact, we’ve been told on several occasions that there is running water, only to find out there isn’t – But thankfully Ted’s a guy who knows how to fix things and isn’t afraid of climbing on to roofs to replumb and refill water tanks (he’s handy to have around – sometimes!). The pricing and charging system here in Peru (mainly in the cities) also reminds me of Masters of the House from the musical Les Miserables, ‘Charge ’em for the lice, extra for the mice, Two percent for looking in the mirror twice, Here a little slice, there a little cut, Three percent for sleeping with the window shut.’ I mean, I don’t blame them, but after a while it starts to get a little tiresome when you know you are being charged extra because of our outsiders status. It also means it’s hard to predict how much things will cost as they just pluck figures from the air – we’ve been charged anything between 7p to £1.00 for an avocado!

Another great divide is the difference between the silence of the mountains, and the continual noise of the towns. I know you could say this about a lot of places, but it’s just the stark contrast between the two that has been so obvious during our time on the Peru Divide. The mountains are so quiet, uninterrupted silence, such peace. The only noise being the bees and a distant stream. With the weather not being too windy, we didn’t even have the blustering of the wind as a constant, the way we have done for a lot of the trip so far. And the silence at night has gifted us many peaceful nights sleep, in the silence of a still calm night under the stars.

But the moment you enter a town there is non-stop, inescapable noise – car drivers honk their horns for any reason (and sometimes I swear it’s just to make extra noise!), dogs are perpetually barking, every shop and cafe has a TV or music on full volume, mobile phones are always on speakerphone, and portable speakers (never headphones) are carried around the streets. The Peruvians also love the megaphone. Any excuse to use a megaphone, at any time of the day or night – in village squares, in shops, from the back of cars and trucks. The noise is seemingly endless, and the locals who live amongst all this noise don’t seem to notice it at all, in fact they almost seem to be unable to live without it as a distraction.

Ted on the other hand cannot stand the noise and gets really irritable, much to my disbelief given he grew up in a house of 8 musicians!

Our time in Huancavelica (one of the bigger towns on the Peru Divide route) was definitely an example of this – as our rest time turned into a couple of sleepless nights. We arrived on the first day of a week-long festival which was something to do with celebrating a bull (and Jesus – obviously!). The whole town seemed to be out on the streets partying. Brass bands were playing and marching, in a fantastic parade of local traditional dress, topped off with sweets for the kids and alcohol (lots of alcohol!). After an hour or so of watching the parade, we moved on, following the rumble of our stomachs to find some local food, but the party and the parade continued. After eating we returned to the parade – it was still marching on, and musicians still playing. We walked the towns streets, taking in the bustling city atmosphere and enjoying the contagious joy of the locals, brought about by the festival, but the parade and the music still continued. We went to bed that night with the sound of the festivities only slightly dulled by our earplugs. At 4am the noise of the festival hadn’t abated. By 5am the fireworks started, continuing for so long that we genuinely wondered whether our hotel was in the middle of a gun fight! The following morning we convinced ourselves that things must have quietened down, but no, these Peruvian party-people really knew how to celebrate and the festivities were continuing. More street parties, more marching bands and parades, more dancing in the streets, more food stalls and endless drinking. It was amazing to be drawn into all the excitement and to enjoy listening to all the music on our rest day. It’s like the whole town was one giant party.

When we left the town the following day, a good 72 hours after we had arrived, there were still pockets of partying going on – it turns out the Peruvians have great stamina for celebrations and don’t mind the noise at all, but we were ready to get back to the silence of the mountains – we just had to pedal back up 1000m+ climb to get there!

The perpetual climbing has been exhausting, but it’s pretty incredible to think that my little legs have somehow managed to propel me up mountain after mountain, over 5000m passes and around hairpin switchbacks that feel like you’re cycling up a helter-skelter. All this whilst perpetually feeling like you are fighting for oxygen in the thin mountain air. Every time you pause and set off again, the lactic acid burns in your legs and breathing is so laboured that you feel the fatigue of the muscles in-between your ribs like a dull ache. When we set off in September, cycling over a bridge or up a curb in the Netherlands felt like an insurmountable task on our heavily loaded bikes, so every pass we have conquered (and there have been lots of them) has felt like a great achievement. Every pass we’ve ticked off made me feel on top of the world, and I created a ritual of celebra-tea (i.e. celebrating with a warm drink of tea from my flask at the top) to mark the occasion.

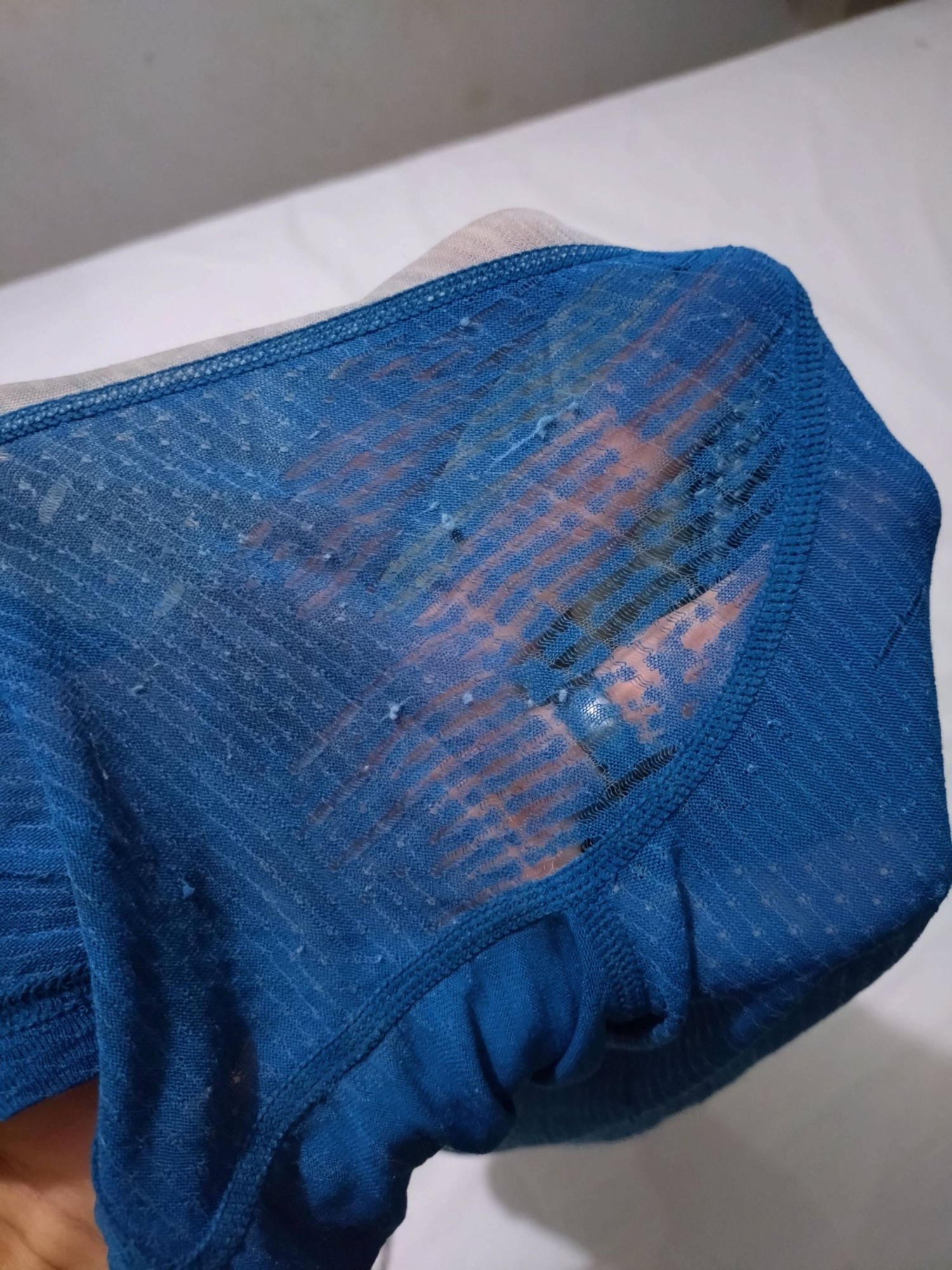

This feeling of physical strength can, however, be wiped out entirely by the stomach bugs that have continued to plague us. Believe me when I say that as you slump on a dirty bathroom floor, face resting against the cool of the porcelain, unable to muster the energy to move back to bed, you feel a million miles away from the athlete you convinced yourself you were when ticking off a couple of 5000m passes in a day. So our time on the Peru Divide has also been peppered by forced rest days due to sickness, but despite how awful those days have felt, we have thankfully been able to get back on the bikes, wobbly and weak, but within 24 hours. And the occurrences of illness have become less frequent as our gut microbiomes have become more accustomed to all the bugs here.

It’s not just our physical health that has felt divided by the Peru Divide, there have also been times when our mental strength has hit rock bottom. There were days when climbing yet another 1500m felt too much, the exhaustion and tiredness grinding us down. For Ted, this usually appeared as getting shouty and angry at inanimate objects for seemingly no reason, his frustration being taken out on anything and everything. For me, it’s an abrupt outpouring of tears and feelings of not being enough – Not strong enough, not helpful enough, not fast enough, not useful enough, not tough enough, not clever enough, not brave enough. And when we fall into a slumps like this, we both find it hard to pull ourselves out of them when we don’t have our home comforts to fall back on – I can’t just go for a run to shake it off, or spend an hour in the kitchen chopping away the frustrations, Ted can’t retreat to the shed or head out to tinker and bash out the Mini. It’s a hard learning process to accept that the reactions to our exhaustion and frustrations are completely normal – crying my way up a hill, or having a paddy about not wanting to get on my bike in the morning really doesn’t feel like acceptable behaviour for a 37 year old – but I know that if I rationalise it, it is just the exhaustion taking over. In hindsight I know that it is perfectly okay given that what we are doing is hard, but it doesn’t make it any easier to accept in the moment. I mean it’s nothing serious, nothing that isn’t usually sorted out with a little time to myself and a good snack. And tea.

For a lot of our time on the Peru Divide good snacks have been in the form of delicious avocados – pre-smashed by the journeys along bumpy roads. In fact, the avocados are so good here that I genuinely worry they will have ruined avocados in the UK for me. The versions we get in the UK are a taste-less, cream-less, rock hard or smushy versions of the avocado perfection here in Peru. They are like the Goldilocks of avocado – not too hard, not too soft, always perfectly ripe – the stone rolling out of the middle the moment they are cut in half. Truly delicious.

The shops are generally still full of the ultra processed, wrapped in plastic substances parading as food, that we’ve seen across all of South America so we’ve continued to stay clear of these as much as possible. The towns are full of fresh, vibrant, fruit and veg, but up in the remote mountain villages understandably there are only meagre offerings of this stuff, so we’ve mainly been back on a simple oh-so-exciting diet of bread, cheese and dried foods like oats, quinoa and rice. Ted sometimes carries the odd robust veg that will survive the journey, like carrots or onion, so we can jazz up dinner a bit, but it’s a big ask for him to carry extra weight on an already heavy bike, up literally thousands of meters of climbing.

We’ve also experienced both the great divide of the delight and frustration of the Peruvian restaurants. The initial delight being the excitement you feel when seeing that a village has a restaurant after days of the same boring food. In most villages, the community driven, cheap, daily fixed menu lunch is the offering. It’s a great Peruvian tradition that ensures a cheap decent meal for locals and hungry cyclists alike. It usually comprises a hearty broth soup with at least two carbs, a little veg and a googley hunk of meat (which can be easily avoided and picked out!), a main course of at least two carbs, a small token salad and another googley hunk of meat or fish, plus a homemade cordial drink of fruit, herbs and spices that will keep you guessing what the flavour is all afternoon. The main downside is that vegetarian isn’t a concept they grasp here. Even when we asked them to remove the one piece of meat from the dish and replace with eggs, it usually took several attempts of us explaining for the locals to comprehend what we were asking. But the options of dishes offered at the restaurants quickly became very repetitive and all involved meat or fish. It was frustrating that despite all the wonderful fruit and veg they have in Peru, they don’t seem to be very adventurous with what they do with it. The same meals again and again on repeat. The result being that we have eaten eggs and rice, then rice and eggs, then eggs followed by rice, or sometimes for a change it’s rice with eggs mixed in. I’ll be pleased if we don’t see eggs or rice again for a little while.

The final divide we’ve felt is the bitter, sweet feeling of our time in Peru, and South America, coming to an end. With each high altitude pass climbed and descended we made our way every closer to Lima, the capital of Peru, from where we fly to the USA. Every climb ticked off was another day of hard work done, one we were pleased not to have to repeat but also another day closer to the end of our time here in South America. We were torn between the feeling of being pleased to finally stop all the exhausting climbing, but not wanting our time here to come to an end. We wanted to savour every incredible landscape, every view from our lunchtime picnic spot, every perfect campsite. We lingered longer to take pictures, to appreciate the colours of the mineral rocks, to marvel at the jagged cliff faces and stare in awe at the mountains whilst feeling so small stood beneath them. To feel so torn between just getting it done, and wanting to take the time to soak it all in was difficult and the divide only grew bigger, the closer we came to Lima.

The descent from the mountain passes of 5000m down to Lima at sea level was two days of downhill – crazy to experience. But as we dropped closer and closer to Lima the air quality, the enjoyment of riding on the roads and the quality of living for the locals became worse and worse. We opted to hop into a truck for a lift for the last few kilometres into the city centre. Arriving in the more touristy area of Lima felt like getting out in another country – swanky apartment buildings, SUVs, fancy designer clothes stores, coffee shops and polished marble pavements. It was worlds away from the mud huts, a single village tap and the street chickens of the mountain villages. The wealth divide was hard to comprehend. Another great divide, possibly the biggest divide we’ve experienced so far.

So for us, the Peru Divide has been a lesson in many great divides – A lesson in geography, an experience of the mountain life and the city life, a month of training the legs in mountain climbing, a growth in our gut microbiome diversity, a time building mental resilience, an education in savouring and appreciating the now.

As our time in Peru, and South America, draws to an end we are so thankful for all the lessons this magnificent route, country, and continent, have taught us.

Leave a comment